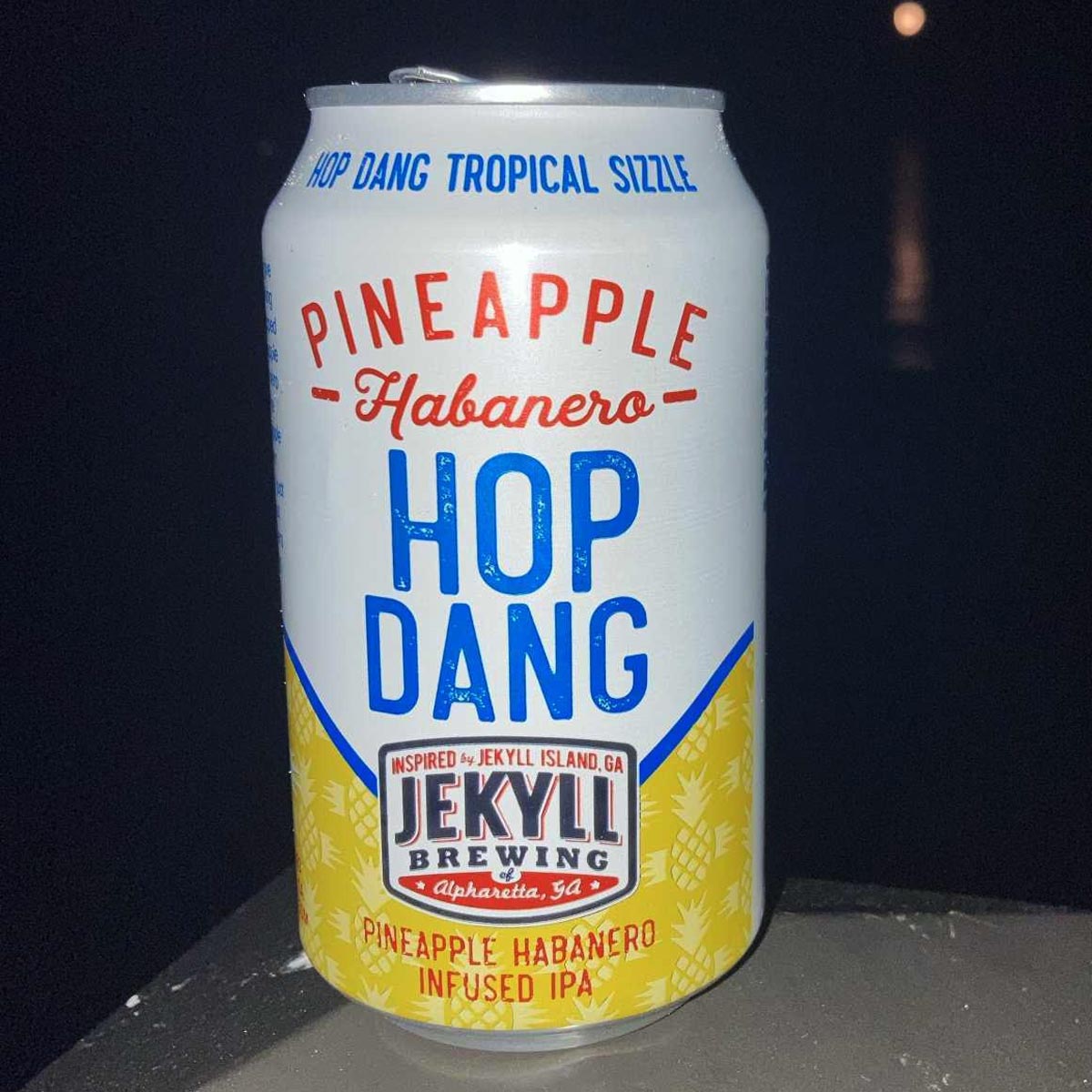

| If I say the word “cider,” your mind most likely turns to fall. That makes sense: Autumn is apple-picking season, traditionally a time when you huddle up by the campfire with a warm, sweet cup of fermented apple juice on a chilly night. But American craft pommeliers, like craft brewers, have been broadening the spectrum of cider and making it a year-round player—especially as a slaker during these remaining days of summer swelter. This will probably come as no surprise to our European readers; we Americans were raised with thick, fruity nonalcoholic apple cider and then graduated to the lightly carbonated, alcoholic version. And just as we spent decades associating beer with only the same pale lagers, the hard ciders we still see at the grocery store—the omnipresent Angry Orchard or Woodchuck—tend to be mouth-puckeringly sweet. Cider’s own craft revolution is starting to change that. “Cider can be sour or funky. It can have other fruit in it. And it can be dry and bubbly as Champagne,” says Beth Demmon, freelance writer and author of The Beer Lover’s Guide to Cider. “There’s a lot of sweet cider, but not all ciders are sweet.” In fact, dry cider is made with the traditional production method, Demmon continues, and it’s what’s pushing craft cider forward: “Most people don’t know about it because it’s not common on grocery store shelves.” When making dry cider, most if not all the residual sugars are converted into alcohol, leaving a bright, effervescent and crisp drink that’s akin to sparkling wine. This takes time and money. The sweet stuff, on the other hand, is easy and cheap: Just throw some sugar in the mix. And no wonder it gets a bad rap. “The people who are focusing on high-quality dry cider are the true artisans,” Demmon says. “Dry cider is the heart of craft cider and its best hope for the future.” Of course, within the broad category of dry cider exists a wide variety of flavors and experiences. This is because, unlike beer, it’s an agricultural product with minimal human intervention. As a result, a cider is primarily characterized by the variety, or blend of varieties, of apples used—and more than 700 types of apples grown are specifically for cider brewing. As Demmon says: “The apple wants to do what the apple wants to do.” So, while some of the Basque ciders from Spain and France that have gained popularity are acidic and tart, dry ciders from England (which, despite having a stronger cider tradition than the US, is likewise awash in mass-produced sweet stuff, such as Heineken NV’s Strongbow) can be bolder and more tannic. American craft cider can run the gamut from sweet to super-dry and crisp to fruited semi-dry blended with cherries, berries and even tropical fruits. Throw in craft beer’s influence of experimentation—I’ve tried a bourbon-barrel-aged dry cider in Oklahoma City and a spicy horseradish cider from Austria—and you can find one to suit any occasion. And when that occasion is summertime refreshment, dry cider checks several boxes. First, it’s crisp, bubbly and, when properly balanced, just fruity enough to be a treat before the clean finish—and, at around 6% alcohol by volume, it’s lighter than wine or your more potent IPAs. Second, it’s naturally gluten-free, which should appeal even to those beer lovers who don’t have intolerance. “Core craft beer drinkers are in their late 30s to mid 50s,” says Demmon. “Most of them can’t pound beers like they used to. Even people who don’t have a gluten sensitivity are switching to cider, which doesn’t make them feel bloated like beer does.” Another reason cider might be the drink of summer: It requires a little outdoor adventure.  Cider in situ at Montana’s Western Cider. Photographer: Rio Chantel O'Reilly/Western Cider Since the industry is still dominated by the sweet and watery macro-ciders, you can’t always just pop into the grocery store to grab a six-pack of dry craft cider. You may be able to go to a local bottle shop or specialty beverage store, or better yet, get to the core of matters and head to your local cidery. “There are working cideries in all 50 states,” says Demmon. “I live in San Diego, which is not apple country, and there’s a cidery near me. Part of the fun is enjoying something that came from the earth and is minimally guided by the hands of humans. Where’s the fun if there’s no risk?” Here are a few of Demmon’s favorite producers, sprinkled throughout the US—and all ship to at least 39 states. Fresh-pressed apple juice and whole fruits are the base of this cidery’s award-winning wares, including Clyde’s Dry, a clean blend of more than a dozen apple varietals.  Bauman’s Oak St. Dry. Photographer: Nathan C. Ward These self-proclaimed “cider nerds” do it all, from the single-varietal dry Ranch Hand to the tart barrel-aged Strawberry Dolgo made with crab apples. Beer lovers might get a kick out of this cidery’s hopped session cider, made with 100% Virginia-grown apples, dry-hopped with Citra and Amarillo. This small-batch brewer looks at apples like wine grapes, focusing mostly on single-varietal ciders featuring heirloom fruit such as Harrison, Jonathan and Golden Russet apples.  The Haykin Family Cider range, all made with single-varietal apples. Source: Haykin Family Cider This cidery focuses on traditional English and French cider apples, including Kingston Black and Harry Masters Jersey. Its tannic Bittersweet is made from 20 such varietals. Four miles south of downtown Ithaca, South Hill specializes in crisp, naturally effervescent dry sparkling ciders, including the Packbasket, a 100% wild-foraged cider. In defense of: Pepper beers | I just returned from a family trip to Jekyll Island, Georgia, a barrier island south of Savannah. It was my eighth time there in about as many years, and on every visit I’ve looked forward to drinking beer from Jekyll Brewing (actually brewed in Alpharetta, an exurb of Atlanta some 350 miles away, but that’s another story). The one I crave most is the Pineapple Habanero Hop Dang Diggity, a variant of its flagship IPA. The sweet bite of pineapple cuts through the sharp bitterness of the hops, yielding to a gentle sweetness and then, just at the finish, the smooth burn. Pepper beer, or chili beer, might sound like a niche style based on a dare, but it’s really one of beer’s broadest categories. Spicy peppers—usually jalapeño, serrano or habanero, but sometimes others—can be added to any style of beer to lend it a vegetal earthiness, slight sweetness and signature heat.  My summertime hero: An IPA made with 100% pure pineapple juice and freshly cut habaneros. Photographer: Tony Rehagen/Bloomberg That sizzle is precisely why drinkers tend to steer clear of pepper beers, especially given that alcohol tends to amplify spiciness. Then, of course, it can all go wrong—overwhelming heat or worse, not enough, leaving a brew that just tastes like a bell pepper. But when the spice is just right, a chili beer is a thing of beauty. Some of my favorites include Confluence Brewing’s crisp and fiery Blue Corn Lager Con Chiles (brewed in Des Moines, Iowa); Modist’s Ritual Night Mexican dark chocolate stout, with vanilla, cinnamon and ancho kick (Minneapolis); and Prairie Artisan Ales’ Spicy Watermelon Girlfriend sour (Krebs, Oklahoma), which is the perfect blend of tart and tangy, with a searing finish that makes you thirst for the next sip. And to this day, I mourn the loss of Huck’s Habanero Apricot Wheat from the defunct Mark Twain Brewing (Hannibal, Missouri), a crushable blend of fruit, malt and fire (RIP). To me pepper beer works best when it’s a balance of fruity sweetness and Scoville scale might—which is why, while I’m a year-round flame shooter, I really crave chili beer in the summer when I’m outside. It might seem counterintuitive to fight heat with heat, but adherents to spicy bloody marys, hotter micheladas and many equatorial types of cuisine know that the right amount of spice triggers your body to cool down when it feels like your mouth is on fire. Unfortunately, this year when I went looking for my poolside Pineapple Habanero buddy, I found that Jekyll Brewing had unceremoniously closed in May. Needless to say, I’ll be on the lookout for another beach burner. But if you happen to have one in mind, email me at topshelf@bloomberg.net. |